Healing Through Art - Part One: My Story

If you prefer to listen to this episode, click here.

Today I'm working on my presentation on Healing Through Art for the virtual Conference on Religious Trauma next month, and I wanted to start by sharing my experience of using art as a tool for reclaiming my story and rewriting my narrative.

If you felt yourself tense up at the idea of creating art, I want to reassure you: many people I've met over the years have told me that they're not creative. Despite their assertion, I believe we are all born creative, or at the very least, with the capacity to be creative. If we’re lucky, we grow up in an environment where the adults around us encourage and foster that creativity.

In their paper Creativity and Cults from Sociological and Communication Perspectives: The Processes Involved in the Birth of a Secret Creative Self, Miriam Williams Boeri, Ph.D. and Karen Pressley state that “Creativity […] is partially dependent on recognition of and acceptance by those who assign value to one’s creativity.”

However, for many people who have experienced high demand religions, groups, or abusive family dynamics, their creativity was diminished, or outright discouraged. This is because creativity is not only inherently an expression of our inner selves, but it is associated with the generation of new, perhaps divergent, ideas. Therefore, if our inner self and creativity are not in alignment with glorifying the abusers who seek to control those in their congregations, groups or families, then it is seen as a threat.

How is creativity a threat?

In his 2015 paper Intuition and Creativity, Shoaib Ul-Habiq says,

Creativity, as an individual level construct, is defined as the production of novel, useful ideas, new products, services, processes or solutions. It refers to both the process of idea generation or problem solving and the actual idea or solution (Amabile, 1983; Shalley, 1995). Johnson (1972) suggested that creative activity may exhibit several dimensions including sensitivity to problems on the part of the creative agent, originality, ingenuity, usefulness, and appropriateness in relation to the creative product, and intellectual leadership on the part of the creative agent.

Others view creativity as a largely unstructured process which is grounded in the intellectual capacity to generate divergent thinking, remote associations, rich imagery and primary process (Guilford, 1967; Mednick, 1962; Rothenberg, 1987; Suler, 1980).

The two points that are most important to highlight in the above are novel, useful ideas and divergent thinking.

According to a basic dictionary definition, creativity means “the ability to transcend traditional ideas, rules, patterns, relationships, or the like, and to create meaningful new ideas, forms, methods, interpretations, etc.; originality, progressiveness, or imagination” (Dictionary.com)

In her book Bounded Choice: True Believers and Charismatic Cults, Dr. Janja Lalich states that the cult leaders define what and who is creative. However, you can substitute whatever abusive power dynamic for the following, and it could still be true to many people’s experiences:

The expression of any thought—be it through song, painting, story, or other craft—is generally discouraged, unless that expression enhances thoughts the leaders (the power elite) have already expressed. Original personal thoughts contrary to the cult’s meaning system are forbidden, and the expression of such private thoughts cannot become public. For example, musicians and songwriters are encouraged to compose music for their leaders’ lyrics; writers are required to craft stories that express the world views of those in power. This power dynamic in the cultic milieu supports the cult’s hegemony, and inhibits any questioning of the leader’s naming of creativity.

According to Boeri and Pressley, “If others—usually the leader—do not identify a cult member as creative, the member cannot continue to have a creative self without birthing a secret creative self.”

Growing up in a cult, my expression of self was a threat to my parents, my faith community and the closed society I was raised in. Now members of the Unification Church might counter and say that creativity is actually very much encouraged. After all, in the 1970’s there were music groups like Sunburst and today they have the band Sonic Cult. The Church also owns the Manhattan Center, where a number of creative projects were attempted over the years. In Korea they founded both the Sunhwa Arts School (originally founded as the Little Angels School) and the Universal Ballet.

On a more local level we had arts festivals for the Second Generation where we shared our music, visual arts and films. Back in 2005 I even helped create a workshop for young actors. But, again, creativity was only encouraged only if it glorified Rev. Moon, his version of God, and his vision of the “ideal world”. In fact, our mission, when engaging in the arts, was to take them over from the “Fallen World.” If our creativity didn’t have that at its center, it was considered of Satan.

In 2010, a survey respondent for the Cultic Studies Review described their experience thusly: “Creativity wasn't suppressed... it was co-opted, harnessed, used, channeled... from an emotional level, I want to use the word ‘raped’….”

I kept my creative side mostly hidden, and therefore did not experience much of what the respondent did in terms of the abuse of their creativity. However, I do think that their words are important to keep in mind when thinking of the kinds of creative expression allowed in cultic environments.

The birth of my secret creative self

According to Boeri and Pressley “a cult member might express [a creative] thought or show the symbolic expression of a thought (e.g. a song, story, drawing) only to a trusted cult member or to an outsider who shows appreciation. In these cases, a creative self may have to be nurtured in secret by some cult members who do not want to expose their tangible expressions of creativity to the judgment of cult leaders. This process leads to the birth of a secret creative self.”

The creation and suppression of my creative self was an incremental process that occurred over many years. My cult identity was supposed to be kept hidden from the outside world, but the true “inner self” was something that I also learned to keep secret.

Growing up, my mother tried to impress the importance of my identity on me. She said that I was different, that I had a mission, and that I had to be very careful about who knew who I was - otherwise Satan would attack me. It was like being born with a secret identity, where I was constantly under threat by the “outside” and “Satanic” world, which would seek to corrupt me. Therefore my younger siblings, myself, and all of the other Second Generation, whom we called Blessed Children, were brought up believing that we needed to be separate from the evil, outside world.

In order to achieve this, many members lived together either in communal living spaces or near one another in closely knit communities. Some communities even started their own schools so that their children didn’t have to attend public schools and fraternize with satanic children. My siblings and I didn’t grow up in one of those communities. For many of our formative years, we were two hours away from the closest Church family. This meant that we grew up in a strange liminal space where we had to live within the world but were not allowed to “be of it”.

This meant I felt a strong sense of otherness, both in and out of the cult, and struggled to form connections with others. I moved through the world in fear of others, initially only allowing myself to be vulnerable and create friendships in the rare sanctioned spaces that my faith and family allowed. I strove to involve myself in every Church activity that I could, because only when I was with other Blessed Children was I supposedly allowed to “be myself.”

Except that I wasn’t. As I grew older, the more I questioned and began to see cracks in the facade of faith. But, in the Church, to question what we were taught was to invite Satan and the evil Spirit World into your mind; to fend off evil, one must quiet the questions and dive further into the readings and teachings of Rev. Moon, whom we were taught to call True Father. As a reflex, I was ashamed and hated myself for questioning and thought that I must certainly be evil.

I knew that my art was evil; I had known that from a young age. Anything that the Church saw in me that was not within the realm of acceptability was shamed out of me. As a result, I was less comfortable showing anyone who I really was, Church or no. There were only a few safe people with whom I could share my struggles, and the art that came out of it. It was in those few safe spaces that the “secret creative self” flourished.

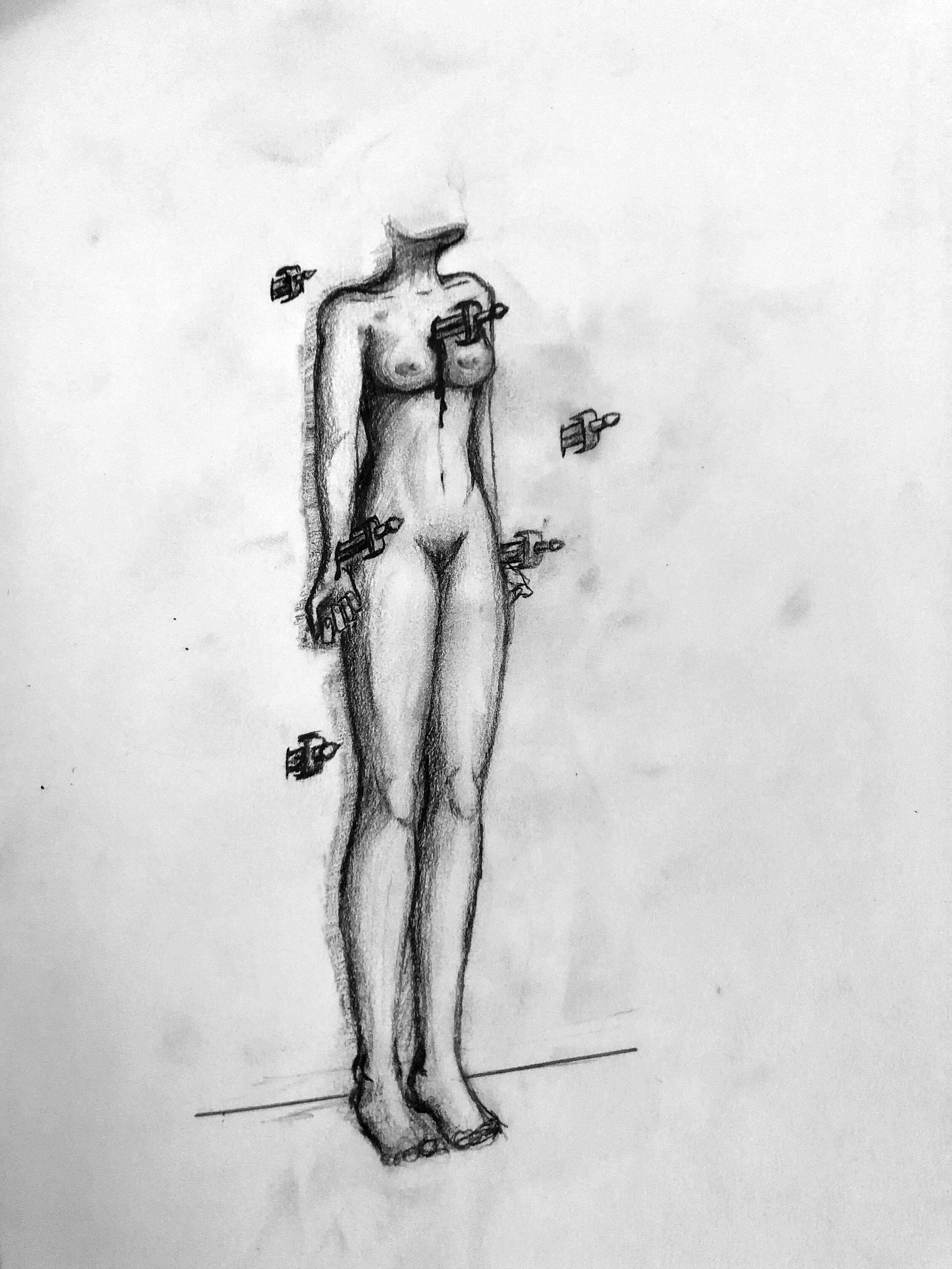

At the time I didn’t have words to describe what I felt. I hadn’t learned the language of trauma or healing; all I knew was the narrowly prescribed language of the Church. And yet, as you can see, some of the images from my high school sketchbook clearly describe everything that I was thinking and feeling about my world:

Leaving the Church

At 19 I found myself on a terrifying personal precipice. I didn’t know if I believed in the Unification Church’s version of “truth”, but with no safety net outside of the Church community, and with a deep fear of the outside world, I didn’t know where to turn.

Additionally, growing up, the Church had taught me that Rev. Moon would choose my spouse. In the Unification Church, one didn’t date. Everything was separated by gender, and we referred to one another as brother and sister in order to emphasize platonic relations. The Church had a word for sex before marriage: falling. To fall was the greatest sin that could be committed.

And at 19 I was pressing against my eligibility expiration date. Friends asked me when I was going to join the “ring club,” and others would caution and say, if “you don’t hurry all the good ones will be gone.” That I was still on the market meant that I, apparently, was not one of the good ones.

Then news came: The aging Rev. Moon, who had directed all of the marriages within the faith from before my birth until I was 15, announced shortly before Christmas that after four years of having the parents Match the Blessed Children, he was stepping back in. This, perhaps, for the last time.

My parents were breathless with agitation. They had tried, without success, to find me a Match and were wondering if things might be hopeless. My mother sat me down and said, “If Jesus came to you and said he had found your perfect match, would you turn him down? Now how much more is True Father?”

How could I say no? I simply had not gotten to the point in my journey where I knew how to leave the Church.

A few days later I found myself married, or Blessed in Church language, to a complete stranger from another country.

That choice ended up being the final straw in breaking my faith, and the next two years found me struggling to extricate myself from my marriage. As I struggled, the Church community didn’t rally to support me or save my marriage. Rather, the community turned its back on me. After all, I had “broken the Blessing,” an unforgivable sin.

The Church taught us that to leave the faith was to open ourselves to death. Growing up they had regaled me with stories of lightning strikes and traffic accidents where the unfaithful had met their doom. So there I was, alone, rejected from the tribe that I had dared to question, and afraid of a very real death.

In the dangerous wilds of the outside world I faced the difficult task of integrating into a world that I had been taught to shun, and to accept the fact that I was no longer a Blessed Child with a secret identity. Who was I really? And how did I connect with the world?

Shedding an Identity and a Language

After being rejected by the community of my birth, I had a genuine fear of rejection from the outside world as well. I was so afraid of being judged for what had happened to me, that for a long time I tried to pretend that I was normal and didn’t tell anyone who I really was. “No one would understand,” I told myself. “They would think I was weak, stupid, or both”.

Over the years, as I distanced myself from the Church, I shed both the language and the identity that had been foisted upon me. But it still took much learning and healing before I had the capacity to express and understand my experience in verbal language. In the interim I turned, again, to art.

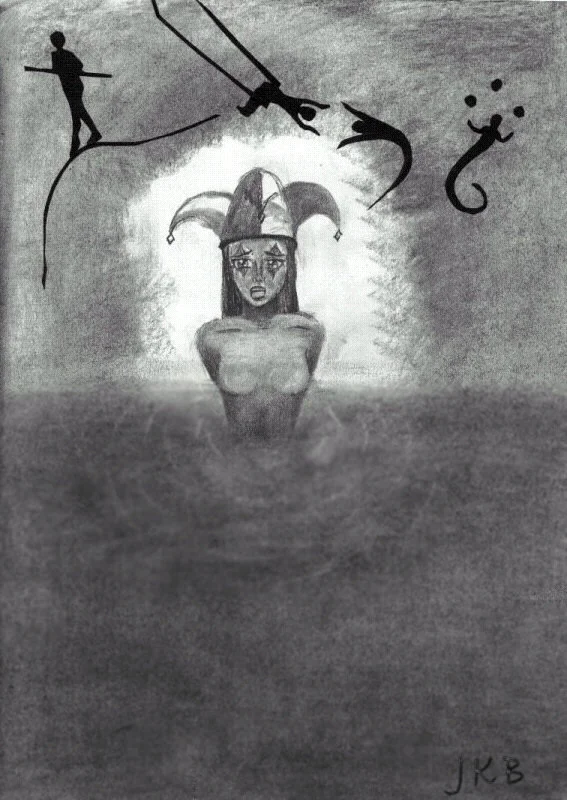

A painting I did for a college assignment of “Monsters.”

Although I tried journaling, painting and poetry, the thing that felt the most radical was picking up a camera and turning the lens on myself. After all, growing up as I did, seeing myself for myself had been forbidden. In that environment, who I was, how I felt, what I thought, and who I married was to be interpreted by the cult.

In the beginning, I felt immense amounts of guilt when I photographed myself. The images always came out looking dark, sad, depressed. “Who was I to be sad?” the voice in my head would say. “After all, I had escaped, gotten a cute apartment, a job that paid my rent. I had even found a nice boyfriend. What did I have to be sad about?”

At the same time, the voice in my head accused me of being vain for photographing myself, of trying to attract the wrong kind of attention. Sometimes it threatened me with the fear of retribution from the cult. I didn’t realize that this was the voice of the religion in my head, still trying to keep me from experiencing myself.

Despite that old voice, I kept taking pictures. And for a long time I hardly recognized myself in the images. But perhaps it was my way of trying to document my own existence for the first time.

Even still, for many years I felt as though I was circling around my truth. I didn’t know how to say, “This is what happened to me.” Not verbally, and not in my art. In fact, I didn’t even have the capacity to acknowledge that I had been raised in a cult. That word was something that the Church had taught me to believe was a false accusation levied against the Church by the Satanic “outside world.” I also didn’t know that what I had experienced growing up was considered abuse.

Then in 2012, Rev. Moon died. Even after five years of being out of the group, his death caused something inside of me to crack open. With his death, I realized that I’d had another unacknowledged fear: that, somehow, Rev. Moon could still hurt me even after my escape.

But now the man who had controlled so much of mine and my family’s lives could no longer hurt me. For the first time since I’d left, I realized that I was beginning to feel safe. And I needed to tell my story.

Initially I tried writing, but still didn’t know how to explain what I had experienced. I tried penning essays that detailed my experiences and the reasons why I left the Church. But I still didn’t have the language to describe the trauma, or the education to even truly understand what had happened to me. I didn’t understand what coercive control or thought reform looked like, and had simply normalized them into my upbringing.

Again, it was only with art that I felt like I could express my experience.

At first, fear nearly overwhelmed me. “How dare I?” I thought.

Then I realized that the voice was my old conditioning; I was still silencing myself long after the Church was there to do it for me. But I wondered: if by remaining silent, was I also being complicit? And so I decided to speak in the only way that I then knew how. Thus my Burdens of a White Dress project was born.

It’s a series that now comprises over 60 images exploring the feminine experience of growing up in a high-demand group, as well as the intersections of purity culture, coercive control, and the sexual, mental and emotional traumas that occur as a result. Most of the images are self-portraits, and they use red, black and white as both a color scheme and the primary symbolism with which I explore these issues.

For years, I struggled against shame and the internalized cult voice to make each image. Today I can look back at both this project, and the images that came before it, and see that I wasn’t just ashamed of taking photos of myself. I was ashamed of my entire story. But creating it was an important step in my healing.

The beginning of healing

By using art, I was able to name the wound that I had no language for. Eventually I delved into the education that would give me the framework and language to understand my experience on an intellectual level. But I believe that many of us understand our experiences on a sensory level that supersedes language.

Creating the work gave me the tools I needed to begin writing more in depth about my story, and to start speaking about it on social media and at conferences. I’ve also returned to poetry, creating black out poetry with Church literature as a reclamation effort.

I wouldn't have been able to do any of this without having first allowed myself to explore my feelings and experiences through a more visual art medium first.

But perhaps was the most healing was the connection that I was able to create through sharing my work. The first time, I was so afraid I nearly blacked out in a panic. I was at an artist’s workshop and slid my prints across a table to the woman who was sitting across from me. She looked at the images very quietly for a moment and then up at me with incredible sadness.

“These photos remind me of me.” Then she told me her story, and a new kind of connection was forged.

Almost without fail, when I share my work and my story, others share their stories in return. A dialogue opens up. I begin to hear that in seeing my work, others find the strength to break through their fears, own their voice or access the words with which they needed to share their stories.

Every single one of us here has suffered something that has become a defining part of our stories. And every one of us has also probably been afraid to be vulnerable and share those parts of us. But when we find safe spaces to create the art that expresses our stories and our truths, we can find healing and give others permission to explore their own healing as well.

In my next post I will talk more about the role that creativity has in healing, as well as the research behind it.

If you’re interested in joining me at the Conference on Religious Trauma , you can sign up at https://pheedloop.com/CORT/site/. Use the code MAIL15 for a $15 discount!

If you have been in ANY high control group or religion, share your story with the hashtag #igotout. Share on your own platform OR if you need to be anonymous and / or would like support, there are resources at the I Got Out website.

When you see a survivor share their story, let them know they have been heard. This is such a meaningful part of the movement. We all need to know we're not alone.

If you know someone who has been harmed by a high demand group, share #igotout posts you think would help them.

Together we can bring awareness to how many of us have been harmed by high control organizations and end the shame or stigma we might feel about our experiences.

Tell your story.

Impact lives.

Change the world.

Find out more at igotout.org

Listen to the episode here: